Sergio c. Fanjul Interview w/ Byung-Chul Han (Oct 2021)

Byung-Chul Han: ‘The smartphone is a tool of domination. It acts like a rosary’

Byung-Chul Han: ‘The smartphone is a tool of domination. It acts like a rosary’

In this exclusive interview with EL PAÍS, the South Korean-born philosopher discusses digital subjugation, the disappearance of ritual and what ‘Squid Game’ reveals about societyThe material world of atoms and molecules, of things we can touch and smell, is dissolving away into a world of non-things, according to the South Korean-born Swiss-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han. We continue to desire these non-things, and even to buy and sell them, Han says. They continue to influence us. While the digital world is increasingly blurred with what we still consider the “real” world, our existence is ever more intangible and fleeting, he believes. The best-selling thinker, sometimes referred to as a rockstar philosopher, is still meticulously dissecting the anxieties produced by neoliberal capitalism.

By combining quotations from great philosophers and elements of popular culture, Han’s latest book Undinge (or Nonobjects), which is yet to be published in English, analyzes our “burnout society,” in which we live exhausted and depressed by the unavoidable demands of existence. He has also considered new forms of entertainment and “psychopolitics,” where citizens surrender meekly to the seduction of the system, along with the disappearance of eroticism, which Han blames on current trends for narcissism and exhibitionism.

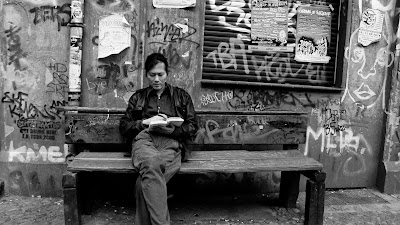

This narcissism runs riot on social media, he believes, where the obsession with oneself makes others disappear and the world becomes a simple reflection of us as individuals. The philosopher strives to recover intimate contact in everyday life – he is known for his interest in gardening, making things with his hands and sitting in silence. He despairs of “the disappearance of rituals,” which also makes entire communities disappear along with them. We become lost individuals, in sick and cruel societies.

Byung-Chul Han conducted this interview with EL PAÍS by email in German, which has subsequently been translated and edited for clarity.

Question. How is it possible that in a world obsessed with hyperproduction and hyperconsumption, at the same time objects are disappearing and we are moving toward a world of non-things?

Answer. There is without a doubt a hyperinflation of objects, meaning they are everywhere. However, these are disposable objects that we cannot really bond with. Today we are obsessed not with things, but with information and data, that is to say, non-things. Today we are all infomaniacs. We even have the concept of datasexuals [people who obsessively collect and share information about their personal lives].

Q. In this world you describe, one of hyper-consumption where relationships are lost, why is it important to have objects that we love, and to establish rituals?

A. These things are a support structure that provides peace of mind in life. Nowadays, that is often obscured by information. The smartphone is not a thing. It produces and processes information, and information gives us the opposite of peace of mind. It lives off the stimulus of surprise, and of immersing us in a whirlwind of news. Rituals give life some stability. The pandemic has destroyed these temporal structures. Think of remote working. When time loses its structure, depression sets in.

Q. Your book states that in a digital world we will become “homo ludens,” focused on play rather than work. But given the precariousness of the job market, will we all be able to access that lifestyle?

A. I have talked about digital unemployment. Digitalization will lead to mass unemployment, and that will represent a very serious problem in the future. Will the human future consist of basic income and computer games? That’s a discouraging outlook. In Panem et circenses [or Bread and Circuses], [Roman poet] Juvenal refers to a Roman society where political action is not possible. People are kept happy with free food and entertainment. Total domination arrives when society is only engaged in play. The recent Korean Netflix show Squid Game points in this direction.

Q. In what way?

A. [In the series] the characters are in debt and agree to play this deadly game that promises them huge winnings. The Squid Game represents a central aspect of capitalism in an extreme form. [German philosopher] Walter Benjamin said that capitalism represents the first case of a cult that is not sacrificial but puts us into debt. In the early days of digitalization, people dreamed that work would be replaced by play. In reality, digital capitalism ruthlessly exploits the human drive for play. Think of social media, which deliberately incorporates playful elements to cause addiction in users.

Q. Indeed, smartphones promised us a certain freedom... but are we not in fact imprisoned by them?

A. The smartphone today is either a digital workplace or a digital confessional. Every device, and every technique of domination, generates totems that are used for subjugation. This is how domination is strengthened. The smartphone is the cult object of digital domination. As a subjugation device, it acts like a rosary and its beads; this is how we keep a smartphone constantly at hand. The ‘like’ is a digital “amen.” We keep going to confession. We undress by choice. But we don’t ask for forgiveness: instead, we call out for attention.Surveillance is increasingly and surreptitiously imposing itself on everyday lifeQ. Some fear that the Internet of Things could one day mean that objects will rebel against human beings.

A. Not exactly. The smart home of interconnected objects represents a digital prison. The smart bed with sensors extends surveillance even during sleep. Surveillance is increasingly and surreptitiously imposing itself on everyday life, as if it were just the convenient thing to do. Digital things are proving to be efficient informants that constantly monitor and control us.

Q. You have described how work is becoming more like a game, and social media, paradoxically, makes us feel freer. Capitalism seduces us. Has the system managed to dominate us in a way that is actually pleasing to us?

A. Only a repressive regime provokes resistance. On the contrary, the neoliberal regime, which does not oppress freedom, but exploits it, does not face any resistance. It is not repressive, but seductive. Domination becomes complete the moment it presents itself as freedom.

Q. Why, despite growing precarity and inequality, does the everyday world in Western countries seem so beautiful, hyper-designed and optimistic? Why doesn’t it seem like a dystopian or cyberpunk movie?

A. George Orwell’s novel 1984 has recently become a worldwide bestseller. People sense that something is wrong in our digital comfort zone. But our society is more like Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. In 1984, people are controlled by the threat of harm. In Brave New World, they are controlled by administering pleasure. The state distributes a drug called “soma” to make everyone feel happy. That is our future.

Q. You suggest that artificial intelligence or big data are not the incredible forms of knowledge they are promoted to be, but rather “rudimentary.” Why is that?A. Big data is only a very primitive form of knowledge, namely correlation: if A happens, then B happens. There is no understanding. Artificial intelligence does not think. Artificial intelligence doesn’t get goosebumps.

Q. French writer and mathematician Blaise Pascal said that: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” We live in a cult of productivity, even during what we call “free” time. You named it, with great success, the burnout society. Should the recovery of our own time be set as a political objective?

A. Human existence today is totally absorbed by activity. This makes it completely exploitable. Inactivity reappears in the capitalist system of domination as an incorporation of something external. It is called leisure time, and as it serves to recover from work, it remains linked to it. We need a policy of inactivity. This could serve to free up time from the obligations of production and make real leisure time possible.

Q. How do you reconcile a society that tries to homogenize us with people’s growing desire to be different from others, to be in a certain way, unique?

A. Everyone today wants to be authentic, that is, different from others. We are constantly comparing ourselves with others. It is precisely this comparison that makes us all the same. In other words: the obligation to be authentic leads to the hell of sameness.We are constantly comparing ourselves with others. It is precisely this comparison that makes us all the sameQ. Do we need more silence, more willingness to listen to others?

A. We need information to be silenced. Otherwise, our brains will explode. Today we perceive the world through information. That’s how we lose the experience of being present. We are increasingly disconnected from the world. We are losing the world. The world is more than information, and the screen is a poor representation of the world. We revolve in a circle around ourselves. The smartphone contributes decisively to this poor perception of the world. A fundamental symptom of depression is the absence of the world.

Q. Depression is one of the most alarming health problems we are facing today. How does this “absence of world” operate?

A. When we are depressed we lose our relationship with the world, with the other. We sink into a scattered ego. I think digitalization, and the smartphone, make us depressed. There are stories of dentists who say that their patients cling to their phones when a treatment is painful. Why do they do that? Thanks to the smartphone, I am aware of myself. It helps me to be certain that I am alive, that I exist. That’s why we cling to our cellphones in situations like dental treatment. As a child, I remember holding my mother’s hand at the dentist’s office. Today the mother will not offer the child her hand, but a cellphone. Support does not come from others, but from oneself. That makes us sick. We have to recover the other person.

Q. According to the philosopher Fredric Jameson, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Can you picture some form of post-capitalism, now that it seems to be in decline?

A. Capitalism really responds to the instinctive structures of man. But man is not only an instinctive being. We have to tame, civilize and humanize capitalism. That is also possible. The social market economy is a demonstration of it. But our economy is entering a new era, the era of sustainability.

Q. You received your doctorate with a thesis on German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who explored the most abstract forms of thought and whose texts are very obscure to the layman. Yet you manage to apply that abstract thinking to issues that anyone can experience. Should philosophy be more concerned with a world where the majority of the population lives?

A. [French philosopher] Michel Foucault defines philosophy as a kind of radical journalism, and he considers himself a journalist. Philosophers should be concerned with today, with current affairs. In this, I follow Foucault’s lead. I try to interpret today in my thoughts. These thoughts are precisely what set us free.

___________________________________

Carles Geli interview with Byung-Chul Han (Feb 2018)

“In Orwell’s ‘1984’ society knew it was being dominated. Not today”

Speaking in Barcelona, South Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han argues social values have been eroded by consumerist culture

Philosopher Byung-Chul Hal is one of the most recognized critics of the problems caused by the hyper-consumerist and neoliberal society after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In books such as Fatigue Society, Psychopolitics and The Expulsion of Difference (published in Spain by Herder), the South Korean-born German author takes aim at this society and its effects on the individual.

“In Orwell’s 1984 society knew it was being dominated. Today we are not even aware of the domination,” he said on Tuesday at the Center of Contemporary Culture in Barcelona (CCCB). There, speaking about the eradication of difference, the Berlin University of the Arts professor gave his vision of the world today, a world where people exploit themselves, fear otherness and live in “the desert, hell or sameness.”Time worked is time lost, it is not time for ourselvesAuthenticity. According to Han, people sell themselves as authentic “because everyone wants to be different from the rest.” This forces a person to “produce themselves” and this is impossible to do authentically because from “the desire to be different creates sameness.” As a result, the system only allows “marketable differences,” he says.

Self-exploitation. In Han’s opinion, society’s attitude has moved from “we have to do it” to “we can do it.” “We live with the anguish of not always doing what we are able to do.” “Today a person exploits themselves believing they are fulfilling themselves. It is the wicked logic of neoliberalism that culminates in the syndrome of the burned-out worker.” This has a very damaging effect. “There is no one the revolution can attack, repression does not come from other people.” It is the “alienation of one’s self” that can manifest as anorexia, overeating or the over-consumption of consumer or leisure products.

Big data. “Macrodata has made thought superfluous because if everything is countable everything is the same … We are in the middle of dataism: man is no longer in charge of himself but is instead the result of an algorithmic operation that controls him without him realizing it. We see it in China with the concession of visas according to state data, or in face-recognition technology.” Will refusing to share data or be on social networks turn into an act of revolt? “We have to adjust the system: the ebook is made to be read, not so I can be read through algorithms… Or does the algorithm now make the man? In the United States, we have seen the influence of Facebook in the elections… We need a digital agreement that restores human dignity and to consider a basic income for professions that will be devoured by new technologies.”The desire to be different creates samenessCommunication. “Without the presence of another, communication will degenerate into an information exchange: relationships will be replaced by connections, and only connect with the same. Digital communication is just sight, we have lost all our sense, we are at a stage where communication has been weakened like never before: global communication and “likes” are restricted to what is most similar. Sameness doesn’t hurt!”

Garden. “I am different, I am surrounded by analogue objects. I have two 400kg pianos and for three years I have grown a secret garden that connects me to reality: colors, scents, feelings… I have allowed myself to notice the earth’s otherness: earth had weight, everything was done by hand, what’s digital has no weight, no resistance, you can move a finger and there it is … It is the abolition of reality. My next book will be called Eulogy to earth. The secret garden. Earth is more than digits and numbers."

Narcissism. Han believes that “being observed is a central part of our being today.” But the problem is that the “narcissist is blind when it comes to seeing the other.” and without this other “one cannot create a sense of self-esteem by themselves.” Art has also been affected by this trend: “It has degenerated into narcissism, it is at the service of the consumer, stupid and unjustifiable quantities of money are spent on it, it is already a victim of the system.”Earth is more than digits and numbersOthers. This is central to Han’s most recent reflections. “The greater the similarity between people, the greater the production, this is the current logic. Capitalism needs all of us to be the same, including tourists. Neoliberalism would not work if people were different.” To recover our differences, Han suggests “returning to the inner animal, which doesn’t consume or communicate unfortunately. I don’t have concrete solutions. In the end the system might implode by itself… In whatever case, we are living in a radically conformist time… the world is at the limit of its capacities, perhaps it will short circuit and we will recover this inner animal.”

Refugees. On this subject Han is very clear: with the current neoliberal system “refugees do not inspire fear, terror or disgust but are rather seen as a burden, with resentment or envy.”

Time. The way time is used needs to be revolutionized, says Han. “Time worked is time lost, it is not time for ourselves.”