Could the abject be close to Lacan's little object a [objet petit a]? The little object a, which is the 'indivisible remainder' of the process of symbolic representation, functions as the ever-already lost object-cause of desire and, by its overflowing nature, plays an intrinsic role in the symbolic process, the untouchable ghostly embodiment of the deficiency that motivates the desire sustained by the (symbolic) Law.

Unlike the object a, which serves as the constituent blind spot or stain within the order of meaning, the abomination is "radically excluded from the realm of symbolic community and draws me to the place where meaning will collapse": "In my disgust the following element that exists in the pre-object ancient relation is preserved: the ancient violence that separates one body from another body so that it may exist." In other words, the experience of abjection is the precursor to great distinctions such as culture-nature, internal-external, conscious-unconscious, repression-repressed – what is meant by my disgust is not immersion in nature (Mother Nature), but rather a process of violent differentiation, a "disappearing intermediary" between nature and culture, the "formation of culture" that disappears as soon as the subject begins to reside in culture.

Ugliness "is the one who disrupts identity, the system, the order. It is one that does not respect borders, positions, rules", but not in the sense of undermining all cultural divisions by the flow of nature; disgust brings to the surface the "fragility of the law," including the laws of nature, which is why when a culture tries to stabilize, it refers to the laws of nature (regular rhythms: day and night, the regular movement of the stars and the sun, etc.). Encountering disgust is frightening, but this fear has no specific object (such as snakes, spiders, heights), but rather a much more fundamental fear of the collapse of the separation between us and external reality: it is not that the open wound or the dead body frightens us, but that it blurs its internal-external boundary.

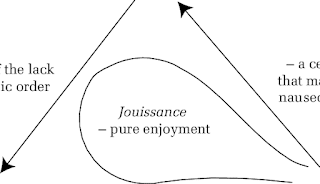

The conceptual matrix underlying the notion of disgust is the idea of a dangerous ground: The area that disgust points to is the source of our vitality—we draw our energy from it, but we need to keep it at an appropriate/correct distance. If we exclude it, we lose our vitality, but if we come too close, we are swallowed up in the self-destructive vortex of madness – which is why my disgust does not step outside the Symbolic, but plays with it from the inside: "Disgust is perverse because it neither abandons nor assumes a prohibition, a rule, a law; it pushes them aside, it confuses and corrupts their targets; he uses them and takes advantage of them so that he can better deny them."

This disgusting/disgusting outburst may also appear in the guise of the "indivisible remainder" of Truth that resists the process of idealization/symbolization – in this context Kristeva speaks of her praise of the residual notion of pagan opponents of Western monotheism; He keeps the movement open forever by preventing the spiritual inclusion of residue creation: "The poet of the Atharva Veda exalts the remnant (uchista), which stains and regenerates, as a precondition for all forms. ' What Remains of the Sacrifice includes name, shape, and world... Both the real and the untrue are in the Flames, death and power.'" The relic here supports the notion of a cyclical universe, what makes the universe reborn. (We find traces of this logic even in Kabbalah: the evil in our universe is considered a remnant of previous universes that God destroyed after He created and was dissatisfied with the result he received – the residue is the ground for the repetition of creation.) It is easy to blame Hegel and Christian monotheism here: they tend to completely eliminate the so-called Evil residue and achieve the Good, they have adopted an exprocity that compensates all of the previous lower stages...

Kristeva's theory of disgust is limited to an attempt to find a middle ground between the symbolic order and the disgust, which she considers two extremes; it neglects the very task of examining how the symbolic order is in terms of disgust. It is not just a matter of the fact that the symbolic order is embedded in the ever-already feminine hora (Kristeva called hora Semyotic) but only the deterioration of the purity of symbolic expressions by the material influence of hora's inherent libidinal rhythms; if the symbolic order now exists, it is certain that it has removed itself from the hora by a violent act of self-differentiation or division. After all, if we are to call this self-differentiation by Kristeva's term 'disgust', then it is imperative that we distinguish between hora and disgust: Ignorance refers to the movement of withdrawal from hora, for the formation of subjectivity it is necessary to retreat from hora.

That is why we must add to Kristeva's diagnosis: the reason why the Judeo-Christian compound "unilateral calls to return to what it suppresses (rhythm, impulse, feminine, etc.)" produces fascism (such as Céline's works) is not because this call falls back from the Symbolic point, but precisely because it covers up the disgust, it covers up the "presuppression" that gives rise to the Symbolic. Such attempts do not want to suspend the Symbolic, they say "let both the (symbolic) cake stop and my stomach be fed", that is, they want to be accommodated in the Symbolic without paying the required price (this price is "precomotion", the ontological confusion of the subject, its conflict, its out-of-control, the violent separation/crack of being differentiated from the natural substance) – this ancient dream is that a universe of masculine meaning also preserves its root in the main substance of hora. To sum up: The element that is covered up in fascism (or even erased from the notebook) is not the Symbolic itself, but the crack that really separates the Symbolic. Figures such as the Jew are therefore needed: if the distinction/rift between the Symbolic and the Truth is not included in the organization of the Symbolic, if it is possible for the Symbolic to "home" the Truth, then the cause of their conflict must be a contingent external invader – and the Jews are more suited to this role than anyone else, because they have rejected paganism, which remains connected to the earth (Offering) by violently asserting the monotheistic symbolic Law...

Of course, we do not necessarily consider the field called "inner experience" to be completely off the agenda; rather, we should focus on a minimum change that the subject empties himself, which is revolutionary in the most fundamental sense. There is a profound irony in the fact that revolution is generally considered to be opposed to evolution: "revolution" actually means the circular motion of the planets. So in evolution, things change, evolve, go somewhere else, and "revolution" returns them to the same place – how, then, did "revolution" mean radical change? The meaning of knocking over an object that stands upright as in Turkish does not exist in English.] Nevertheless, there is a deep meaning in this paradox: in evolution there are changes in the same space, and in revolution this space itself has changed, so that when one returns to the same place, that place is no longer that place, but radically changed. This brings us to the notion of minimum change. The Truth, which Kristeva calls disgust, is disguised as the externality of an abyss that threatens to swallow up and tear the subject apart, so its dialectical counter-move is to focus on a minimum difference—not a gigantic degradation that ruins everything, but a minimal change, but an absolute change nonetheless, a change that leaves nothing the same, even if it doesn't really change anything. "Even if nothing happened, something definitely happened, but we didn't notice it"]Notes:From Disparities (2016)

Turkish: Işık Barış Fidaner

.

And by a prudent flight and cunning save A life which valour could not, from the grave. A better buckler I can soon regain, But who can get another life again?

Archilochus

Monday, May 30, 2022

Symbolic Desire/Disgust

Slavoj Žižek, "The object-cause that drives desire (objet a) and the abject that clouds desire"

Assessing "Reality" 3x

Slavoj Žižek, "Lola's three lives"

Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run (1998) is, in a sense, a postmodern and enthusiastic iteration of Krzysztof Kieślowski's Blind Fortune (1987). Berlin punk girl Lola (Franka Potente) must find a hundred thousand German marks in twenty minutes to save her boyfriend from being killed; Three alternative sequels are enacted:1) Her boyfriend is killed.Also, judging by a series of signs, both Lola and the other people seem to remember previous versions in a mysterious way.

2) Lola is killed.

3) Lola gets the job done, her boyfriend finds the lost money, and the two of them have a happy ending with a hundred thousand German marks gain.While Lola is the exact opposite of Blind Fortune in terms of her adrenaline-fueled exuberant speed and animating energy, the two films are based on the same formal matrix: both films can be interpreted as if only the third story is "real" and the fanciful price that the subject must pay to reach this "real" result is staged in the other two stories.What's interesting about Lola is her tonality: not only her rapid rhythm, her machine-gun-like montages, her use of instantaneous frames, the protagonist's overflowing pulses and vitality, but more importantly, the way these visual elements are immersed in the soundtrack – the continuous techno-musical acoustic rhythm that captures Lola's – and therefore us audience's heartbeat.

While the film's visual grandeur dazzles, let's not forget that those images are subordinated to this musical acoustic (this endlessly exuberant and compelling rhythm) – the only thing that can break that rhythm is an overflowing vitality, and that is Lola's uninhibited cry repeated in each of the three versions.

That's why a movie like Lola could only stand out in a world that included MTV culture. Here the same reversal as proposed by Fredric Jameson in the context of Hemingway's style must be made: it cannot be said that Lola's formal features accurately express the narrative; on the contrary, the narrative in the film was invented to be able to apply this style.

The first words in the film ("the game lasts ninety minutes, everything else is theory") are reminiscent of computer games: Just as there are always three lives in computer games, Lola is given three lives. Thus, "real life" is staged in the guise of a fictional computer game.

Here we must resist the temptation to claim that Lola is inferior culture and Kieślowski's Blind Fortune is high culture: we cannot pretend that Kieślowski has a thoughtful existentialist stance in the face of Tykwer's computer game techno-rock MTV universe.

In a sense, even if this is indeed the case, and even if it is obvious, there is something much more important:The basic matrix of narrative alternative twists is much better hit by Lola: Blind Fortune, who ultimately looks novice and artificial, as if this film is trying to tell her own story by putting it into an inaccurate form, while Lola's form fits perfectly into the context she describes.Notes:

From the Fear of True Tears

Turkish: Işık Barış Fidaner

See Entropy (special page), "Sweat of the brow, sweat of the brow, sweat of the Ancestors", "Finishing is to begin: the exercises of living for the sake of sports, or to remove shackles of the pyramid scheme"

Resisting Subjective Fantasy Through the Objective Subjectivity of Over-Identification

Slavoj Žižek, "I'll be your frog!"

A current beer ad allows us to clarify sexual distinction.

At first, the famous fairy tale is staged: a girl comes to the edge of the stream, sees a frog, gently picks it up, kisses it, and of course the miracle happens: the ugly frog turns into a young and beautiful man. But the story doesn't end there: The young man gives her a harsh look, pulls her to himself, kisses her – and the girl turns into a bottle of beer, with a triumphant air the man holds the bottle in his hand...

The woman's concern is to transform the frog into a beautiful man, that is, into a complete phallic presence (Φ in Lacan's mathems) with her love and attention; the man's concern is to reduce the woman to the partial object that causes his own desire (the little object a in Lacan's mathem). It is because of this asymmetry that "there is no sexual intercourse": either there is a frog with a woman, or there is a beer bottle with a man – a "natural" pair of beautiful men and women can never be acquired. Reason? Because the fanciful support of this "ideal couple" would be inconsistent: the frog wrapped in a beer bottle.

We can resist the penetration of fantasy into us through over-identification. You embrace the multitude of excessively identical incoherent fanciful elements all at the same time and place.

Each of the two subjects is immersed in its own subjective fantasy – the girl imagines that the frog is actually a young man; The man dreams that the girl is actually a bottle of beer. [But the opposite] is not objective reality, but the "objective subjectivity" of the underlying fantasy, which subjects can never take on.

If the frog wrapped in a beer bottle were a painting of Magritte, its title would be "male and female" or "ideal couple." Isn't that the ethical task of contemporary artists? Isn't it to confront the frog hugging the beer bottle while we dream of hugging our beloved?Notes:From the Epidemic of Dreams

Turkish: Işık Barış Fidaner

On Subjectivity and Right Hemispheric "Other-Belief" v. Left Hemispheric "Self-Knowledge"

Slavoj Žižek, "The subject he supposedly believed in"

The subject he is supposed to believe in and the subject he is supposed to know are not symmetrical, because belief and knowledge are not symmetrical: the most radical status of the great Other as a symbolic institution is faith (trust), not knowledge; for faith is symbolic, knowledge is real (the great Other gives a fundamental 'trust' and is based on it). There is always a minimum of 'reflection' in faith, 'believing in what someone else believes' ('I still believe in Communism' means 'I still believe there are people who believe in Communism'), while knowledge has nothing to do with someone else's knowledge. So I can believe through someone else, but I don't know through someone else. That is: when someone else believes in my place because of my inherent reflection of faith, I believe through him; there is no such thinking in knowledge – assuming that someone else knows, I do not know through it.

According to a famous anthropological anecdote, 'primitives' who are said to have 'superstitions' when they are asked about this issue directly, 'Here some people believe...' they immediately postponed the beliefs and passed them on to someone else. We do the same to our children: if we are staging Santa Claus rituals, it is because our children believe (assume so) so that they do not lose hope.

Isn't the same excuse used in the myth that a cynical or dishonest politician suddenly becomes an honest man? – 'I cannot discourage those who believe in him [or me] [the legendary 'ordinary citizen']'. Moreover, doesn't this need to find others who 'truly believe' lead us to label Others (religious or racist) as 'fundamentalists'?

The way faith works is uncanny, it always works under the guise of 'believing from afar': there must be an ultimate guarantor for the faith to work, but this guarantor is always postponed, shifted, never confronted in person. So how is faith possible? How will the vicious cycle of postponed beliefs be broken?

The point is that there is no need for a subject who directly believes that faith will work: you just have to assume it, that is, you have to believe in its existence – either in the guise of a legendary founding figure who is not part of the reality we live in, or in the impersonal guise of 'people believe, believe'.

An important mistake to be avoided in this context is the 'humanist' notion that claims that the belief embodied in things, the belief in things that is postponed, is in fact a reification of direct human belief; accordingly, our task is to reconstitute the creation of 'reification' in a phenomenological sense, demonstrating how the original human belief is transferred to objects... The paradox that must be protected from such attempts at phenomenological creation is that the postponement is initiating and constitutive : there is no direct existing living subjectivity that we can call 'the first owner of it' in order to ascribe the belief embodied in 'social things'.Notes:From the Epidemic of Dreams

Turkish: Işık Barış Fidaner

Saturday, May 28, 2022

Support for Gustavo Petro, Columbian Presidential Candidate

from Wikipedia:

Gustavo Francisco Petro Urrego (Spanish pronunciation: [ɡusˈtaβo fɾanˈsisko ˈpetɾo uˈreɣo]; born 19 April 1960) is a center-left Colombian politician and economist who is serving as senator of the Republic of Colombia.[1][2] At 17 years of age, he became a member of the guerrilla group 19th of April Movement, which later evolved into the M-19 Democratic Alliance, a political party in which he was elected to be member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia in 1991. Petro served as a senator as a member of the Alternative Democratic Pole party following the 2006 Colombian parliamentary election with the second-largest vote in the country. In 2009, he resigned his position to aspire to the presidency of Colombia in the 2010 Colombian presidential election, finishing fourth in the race.[3]After problems and ideological differences with the leaders of the Alternative Democratic Pole, he founded the movement Humane Colombia to compete for the mayoralty of Bogotá, the Capital City of the country. On 30 October 2011, he was elected Mayor of Bogotá in the local elections of the city, a position he assumed on 1 January 2012.[4] On 27 May 2018, he came second in the first round of the presidential election with over 25% of the votes and lost in the run-off election on 17 June.[5] Petro is a front-runner in the 2022 Colombian presidential election.[6] He has promised to focus on climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions that cause it by ending fossil fuel exploration in Colombia.Early lifePetro was born in rural Ciénaga de Oro, in the Córdoba Department, in 1960. His parents were farmers. He was baptized Gustavo Francisco in honor of his father and grandfather.[8] Petro was raised in the Roman Catholic faith and has stated on numerous occasions that he holds this religious belief.[9] Seeking a better future, Petro's family decided to migrate to the more prosperous Colombian inland town of Zipaquirá, just north of Bogotá, during the 1970s.[10]Petro studied at the Colegio de Hermanos de La Salle, where he founded the student newspaper Carta al Pueblo ("Letter to the People"). At the age of 17 he became a member of the 19th of April Movement, and was involved in activities. During his time in 19 April Petro became a leader, and was elected ombudsman of Zipaquirá in 1981 and councilman from 1984 to 1986.M-19 militancyAt a young age (around 17) Petro became a member of the 19th of April Movement (M-19),[11] a Colombian revolutionary organisation movement that emerged in 1974 in opposition to the National Front coalition after allegations of fraud in the 1970 election.[12]In 1985, Petro was arrested by the army for the crime of illegal possession of arms. He was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison.[13][10]EducationPetro graduated in economics from the Universidad Externado de Colombia and began graduate studies at the Escuela Superior de Administración Pública (ESAP). Later, he earned a master's degree in economics from the Universidad Javeriana.[14][15] He then traveled to Belgium, enrolling (but not graduating) in graduate studies in Economy and Human Rights in Université catholique de Louvain. He also has unfinished studies towards a doctoral degree in public administration from the University of Salamanca, in Spain.[16][17][18]Early political careerAfter the demobilization of the M-19 movement, former members of the group (including Petro) formed a political party called the M-19 Democratic Alliance which won a significant number of seats in the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia in 1991, representing the Cundinamarca Department.[19]In 2002, Petro was elected to the House of Representatives of Colombia representing Bogotá, this time as a member of the Vía Alterna political movement he founded with former colleague Antonio Navarro Wolff and other former M-19 members. During this period he was named "Best Congressman", both by his own Congress colleagues and the press.[20]As a member of Vía Alterna, Petro created an electoral coalition with the Frente Social y Político to form the Independent Democratic Pole, which in 2005 fused with the Alternativa Democrática to form the Alternative Democratic Pole, joining a large number of leftist political figures.In 2006, Petro was reelected Senator of Colombia, mobilizing the second highest voter turnout in the country.[21] During this year he also exposed the Parapolitics scandal, accusing members and followers of the government of mingling with paramilitary groups in order to "reclaim" Colombia.[22]Opposition to the Uribe GovernmentSee also: Álvaro UribeSenator Petro has vehemently opposed the government of Álvaro Uribe. In 2005, while a member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia, Petro denounced the lottery businesswoman Enilse López (also known as "La Gata" [the cat]). As of May 2009, she was imprisoned and under investigation for ties to the (now disbanded) paramilitary group United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC). Senator Petro alleged that the AUC financially contributed to the presidential campaign of Álvaro Uribe in 2002. Uribe refuted these statements by Petro but, during his presidential reelection campaign in 2006, admitted to having received financial support from Enilse López.[23]During Álvaro Uribe's second term as president, Petro encouraged debate on the Parapolitics scandal. In February 2007 Petro began a public verbal dispute with President Uribe when Petro suggested that the president should have recused himself from negotiating the demobilization process of paramilitaries in Colombia; this followed accusations that Uribe's brother, Santiago Uribe, was a former member of the Twelve Apostles paramilitary group in the mid-1990s. President Uribe responded by accusing Petro of being a "terrorist in civilian clothing" and by summoning the opposition to an open debate.[24]On 17 April 2007, Senator Petro began a debate in Congress about CONVIVIR and the development of paramilitarism in Antioquia Department. During a two-hour speech he revealed a variety of documents demonstrating the relationship between members of the Colombian military, the current political leadership, narcotraffickers and paramilitary groups. Petro also criticized the actions of Álvaro Uribe as Governor of Antioquia Department during the CONVIVIR years, and presented an old photograph of Álvaro Uribe's brother, Santiago, alongside Colombian drug trafficker Fabio Ochoa Vázquez.[25]The Minister of Interior and Justice, Carlos Holguín Sardi and the Minister of Transport, Andrés Uriel Gallego were asked to defend the president and his government. Both of them questioned Petro's past as a revolutionary member and accused him of "not condemning the warfare of violent people". Most of Petro's arguments were condemned as mud-slinging. The day after this debate the president said "I would have been a great guerrilla, because I wouldn't have been a guerrilla of mud, but a guerrilla of rifles. I would have been a military success, not a fake protagonist".[26]President Uribe's brother, Santiago Uribe, affirmed that his father and the Ochoa brothers had grown up together and were in the Paso Fino horse business together. He then mentioned that he also had many photographs, taken with many people.[27]On 18 April 2007 the Vigilance and Security Superintendency released a communique rejecting Petro's accusations concerning the CONVIVIR groups. The Superintendency said that many of the groups mentioned were authorized by the Departments of Sucre and Córdoba, but not by the Antioquia government; it also added that Álvaro Uribe, then Antioquia's governor, had eliminated the legal liability of eight CONVIVIR groups in 1997. It was also mentioned that the paramilitary leader known as "Julian Bolívar" had not yet been identified as such and was not associated with any CONVIVIR during the authorization of these groups.[28]Death threatsPetro has frequently reported threats against his life and the lives of his family, as well as persecution by government-run security organizations.[29] On 7 May 2007 the Colombian army captured two Colombian Army intelligence non-commissioned officers that had been spying on Petro and his family in the municipality of Tenjo, Cundinamarca. These members had first identified themselves as members of the Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (DAS) the Colombian Intelligence Agency but their claims were later denied by Andrés Peñate, director of the agency.[30]2010 Presidential campaignMain article: 2010 Colombian presidential electionIn 2008, Petro announced his interest in a presidential candidacy for 2010.[31] He distanced himself from government policies and, along with Lucho Garzón and Maria Emma Mejia, led a dissenting faction within the Polo Democrático Alternativo. Following Garzón's resignation from the party, Petro proposed a "great national accord to end Colombia's war," based on removing organized crime from power, cleaning up the judicial system, land reform, democratic socialism and a security policy differing considerably from the policies of President Uribe. On 27 September 2009, Gustavo Petro defeated Carlos Gaviria in a primary election as the Alternative Democratic Pole candidate for the 2010 presidential election.In the presidential election held on 30 May 2010, Petro did better than polls had predicted. He obtained a total of 1,331,267 votes, 9.1% of the total, finishing as the fourth candidate in the vote total, behind Germán Vargas Lleras and ahead of Noemí Sanín.Mayoralty of Bogota (2012–2014; 2014–2015)Mayor Petro in 2012.During Petro's administration, measures such as the prohibition on the carrying of firearms were advanced, which led to the reduction of the homicide rate, reaching the lowest figure of the last two decades.[32][33] In his government, various interventions were carried out by the police in El Bronx sector of the city, where seizures of drugs and weapons were made. During the Petro administration, the Women's Secretariat was created and the LGBTI Citizenship Center was inaugurated, where 49 centers for birth control and abortion care were also created in cases permitted by law.[34]It was proposed as a government policy to conserve the wetlands of Bogotá and plan for the preservation of water in the face of global warming. Following order of the Constitutional Court, began a process of suppression of animal-drawn vehicles used by waste pickers putting many out of work, some were replaced by automotive vehicles and subsidies. In the area of public health, Mobile Attention Centers for Drug Addicts (CAMAD) were created. With these measures, the aim was to reduce the dependency of the destitute in the streets of the sector to the providers of narcotic drugs, providing psychological and medical assistance. During its administration, the District put into operation two primary-care clinics at the San Juan de Dios Hospital, closed in 2001. The Mayor promised that he would allocate resources to purchase the Hospital grounds and reopen one of the buildings of the complex. The project remained stopped due to the Cundinamarca government's suspension of the sale of the properties. On 11 February 2015, as mayor of Bogotá, the protocol ceremony for the reopening of the San Juan de Dios Hospital Complex was finally formalized. The District bought the hospital with a view to reopening it. During his last month in office, before the liquidation of Saludcoop on 1 December 2015, the district had difficulties with the new patients who became part of the EPS Capital Salud.In his government, the application of the Integrated Public Transport System (SITP) began, inaugurated in mid-2012. Likewise, during the administration of Petro, subsidies paid by the District to reduce Transmilenio tariffs were created. In turn, since early 2014 the administration provided a 40% subsidy for the value of the ticket for the population affiliated to SISBEN 1 and 2, for which it allocated 138 billion pesos. This subsidy is not delivered immediately, as it requires registration in a database, and is valid only for 21 passages when using the blue buses of the SITP.The construction of a subway for the city was one undelivered proposal. During his administration, he contracted studies of the subway infrastructure to a Colombian-Spanish company for $70,000 million pesos, which successfully ended at the end of 2014. Approval from the federal government was necessary to begin construction, but the Santos' administration refused to authorize it. The subway plans contracted by Petro's administration were discarded by his successor Enrique Peñalosa, who opted for an elevated railway system with lower investment required and better coverage, allegedly. These claims have been refuted by several independent studies who have found out that both the social and economic cost of an elevated railway system is higher than the original underground railway system planned by the previous administration.RecallPetro in 2013During his administration as mayor, Petro faced a recall process started by opposition parties and supported by the signatures of more than 600,000 citizens. After the legal verification, 357,250 signatures were validated,[35] many more than legally required to start the process.[36][37] On 9 December 2013, he was removed from his seat and banned from political activity for 15 years,[38] by Inspector General Alejandro Ordóñez Maldonado, following the sanctions stipulated by the law. His sanction was allegedly caused by mismanagement and illegal decrees signed during the implementation of his waste collection system.[39] This led to a series of protests citizens who deemed the Inspector's move as controversial, politically biased and un-democratic.[40][41]Despite being granted an Injunction by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which suspended the sanction imposed by Inspector General Ordoñez, President Juan Manuel Santos upheld the removal and Petro was removed from office 19 March 2014.[42] For his temporary replacement, Santos appointed as Mayor the Labor Minister, Rafael Pardo. On 19 April 2014, a magistrate from the Superior Tribunal of Bogota ordered the president to obey the recommendations laid out by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Petro was reinstated as mayor on 23 April 2014 and finished the length of his term.[43]2018 presidential campaignMain article: 2018 Colombian presidential electionPetro and his running mate Ángela Robledo (far left) receiving endorsements from Antanas Mockus (third from left) and Claudia López Hernández (third from right) at an event in Bogotá, during the campaign for the second round, June 2018In 2018, Gustavo Petro was again a presidential candidate, this time getting the second best result in voting counting, in the first round on 27 May, and advanced to the second round.[44] His campaign was run by publicists Ángel Beccassino, Alberto Cienfuegos and Luis Fernando Pardo.[45] A lawsuit was filed by citizens against Duque alleging bribery and fraud. The News chain Wradio made public the law suit 11 July, which was presented to the CNE (Consejo Nacional Electoral, National Electoral Council, by its acronym in Spanish).[46] The state of the law suit will be defined by the Magistrado Alberto Yepes.Petro's platform emphasized support for universal health care, public banking, a rejection of proposals to expand fracking and mining in favor of investing in clean energy, and land reform.[47] Before the runoff, Petro received endorsements from senator-elect Antanas Mockus and senator Claudia López Hernández, both members of the Green Alliance.[48]In the second round of voting, Petro's right-wing opponent, Iván Duque, won the election with more than 10 million votes, while Petro took second place with 8 million votes. Duque was inaugurated on 7 August; meanwhile, Petro returned to the Colombian Senate.[49]He received death threats from the paramilitary group Águilas Negras.[50]2022 presidential campaignMain article: 2022 Colombian presidential electionIn 2022 Gustavo Petro had declared that he will be running in the 2022 elections.[51] Petro’s campaign platform included promoting green energy over fossil fuels and a decrease in economic inequality.[7] He also pledged to raise taxes on the wealthiest 4,000 Colombians and said that neoliberalism would ultimately "destroy the country". Petro has also announced that he would be open to having president Iván Duque stand trial for police brutality committed during the 2021 Colombian protests.[52] Furthermore, he promised to establish the ministry of equality. Following his victory in the Historic Pact primary, Petro selected Afro-Colombian human rights and environmental activist and recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize, Francia Márquez, to be his running mate.[53]Among the key points of his program, he proposes an agrarian reform to restore productivity to 15 million hectares of land to end "narco-latifundism"; a halt to all new oil exploration in order to wean the country off its dependence on the extractive and fossil fuel industries, a plan that has been widely criticized for its fiscal irresponsibility[54][55][56] since this sector accounts for over half of Colombia's export revenues (54.6% as of March 2022[57]); infrastructure for access to water and development of the rail network; investment in public education and research; tax reform and reform of the largely privatized health system.[58] Petro announced that his first act as president will be to declare a state of economic emergency to combat widespread hunger. He is advocating progressive proposals on women's rights and LGBTQ issues.[59] Petro has also stated that he would restore diplomatic relations with Venezuela.[60]Petro with former Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero in 2022During the campaign he faced a campaign by various media outlets seeking to equate him with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and claiming that he plans expropriation measures if he becomes president. In response to the attacks, he signed a public document on 18 April in which he pledged not to carry out any type of expropriation if elected.[61] During a presidential debate hosted by El Tiempo on 14 March, candidates responded to a question about relations with Venezuela and Nicolás Maduro. Whilst other participants responded by stating Venezuela is a dictatorship and expressing reluctance toward restoring relations, Petro replied, "if the theory is that with a dictatorship you can't have diplomatic relations, and Venezuela is, [then] why does this government have relations with the United Arab Emirates, which is a dictatorship, perhaps worse [than Venezuela]?" He also stated that diplomatic relations are established with nations and not with individuals.[62] Whilst Petro has praised former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez for bolstering equality, Petro said during an interview with French newspaper Le Monde in May 2022 that Chávez made a "serious mistake of linking his social program to oil revenues." He also criticised Venezuela's commitment to oil by president Maduro. Petro argued that "Maduro's Venezuela and Duque's Colombia are more similar than they seem", pointing to the Duque administration's commitment to non-renewable energy and the "authoritarian drift" of both governments.[63] General Eduardo Zapateiro, commander of the National Army of Colombia, also severely criticised Petro during the campaign, causing controversy.[64]Petro and his running mate Francia Márquez faced numerous death threats from paramilitary groups while on the campaign trail. Petro cancelled rallies in Colombiaʼs coffee region in early May 2022 after his security team uncovered an alleged plot by the La Cordillera gang.[65] In response to this and many other similar situations, 90 elected officials and prominent individuals from over 20 countries signed an open letter expressing concern and condemnation of attempts of political violence against Márquez and Petro. The letter also highlighted the assassination of over 50 social leaders, trade unionists, environmentalists and other community representatives in 2022. Signatories of the letter included former Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa, American linguist and philosopher Noam Chomsky and member of the French National Assembly Jean-Luc Mélenchon.[66]During the campaign, Petro received support from international politicians, such as former Uruguayan president José Mujica and former Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero.[67][68]

Thursday, May 26, 2022

Happiness is a Warm Gun...

Slavoj Žižek, "Living to Death"

What ethical stance is appropriate for the complicated situation we are experiencing today, which consists of health crisis, global warming, social-economic and similar conflicts?

The first figure that comes to mind is the experts, who are engaged in a special task imposed by the authorities; an expert may recklessly ignore the broad social context of his or her activity.

The second figure that comes to mind is the radical-like intellectuals; these critics of the existing order know very well that their criticism will have no real effect because they take refuge in the comfortable position of moral superiority.

So how do we continue our lives after we get rid of the illusion that critical stances have made us cringe?

It is not enough for us alone to accept our reality: as we are fascinated by the final states of our civilization, we become spectators deriving morbid pleasures from the breakdown of normality...

The time dimension should always be kept in mind: even when we panic when we talk about major catastrophes (pandemics, global warming, etc.), we as a rule postpone them to a not-so-near future (ten years from now) – "if we don't act soon, we may be too late" – or at least we postpone the disaster to a distant region (corals are disappearing in Northern Australia, the glaciers are melting...). But the global pandemic has hit us all with all its might and has greatly paused our social lives.

What kind of existential stance does such a situation entail? The main chorus of Rammstein's song "Dalai Lama" says:Weiter, weiter ins Verderben Wir müssen leben bis wir sterbenThis is the most proper stance you can adopt in a time when the global pandemic has reminded us all that we are finite and mortal. Our life depends on the interaction of many factors (which seem vague to us) (which seem contingent to us). The main issue we have every day is not that we can die; the main thing is that our life drifts into uncertainty, causing a permanent crisis and eroding our will to continue.

Continue, continue towards

destruction It is imperative that you live until you die

(English: Yerçek)

As we are fascinated by the end of our civilization by total catastrophe, we become a spectator deriving morbid pleasures from the breakdown of normality; this fascination is often fueled by a folly guilt (we deserved the punishment of the global pandemic for our corrupt lifestyle, etc.).

At the moment, on the one hand, vaccination is promised, and on the other hand, variants of the virus are diversifying and spreading, so that we are experiencing a collapse that is postponed forever. Notice how the exit door has shifted: in the spring of 2020, officials could say "things are going to get better in two weeks"; when autumn came, this period became two months; It is now being said that things will get better in six months (things could get better in the summer of 2021 or later; voices are already being heard postponing the end of the global pandemic to 2022 or even 2024... [n. it's still not over!]

New news comes in every day – vaccines are effective against new variants, but maybe not; The Russian Sputnik vaccine is not good at all, but now we understand that perhaps it is very good; there was a lot of delay in the supply of vaccines, but most of us would still be able to get vaccinated by the summer...

These waves that come and go endlessly, the waves that are crossed by the waves that are crossed by the waves that are crossed by the waves that are crossed by the waves that are crossed... Including its entire lineage: cynicism/cynicism/sarcism] of course produces its own pleasure and makes it easier for us to survive in this miserable life.

Rammstein's statement that "you must live until you die" draws the way out of this cul-de-sac: Our fight against the global pandemic should not be an excuse for withdrawing from life, but should cause us to live at the highest intensity.

Who is left alive today than the millions of health workers who continue to work every day, risking their own lives? Many of them died but lived to death. Their concern is not to sacrifice themselves for us and collect our hypocritical praise. And it cannot be said at all that they are survival machines reduced to bare lives – they are the most alive today.Excerpt from The Last Exit to Communism

[Bridge]

The father is now holding onto the child

And has pressed it tightly against himself

He doesn't notice its difficulty in breathing

But fear knows no mercy

So with his arms the father....

The father is now holding onto the child

And has pressed it tightly against himself

He doesn't notice its difficulty in breathing

But fear knows no mercy

So with his arms the father....

Squeezes the soul from the child

Which takes its place upon the wind and sings:

[Outro]

Come here, stay here

We'll be good to you

Come here, stay here

We are your brothers

Wednesday, May 25, 2022

Monday, May 23, 2022

Ukraine Again

Slavoj Zizek, "We must stop letting Russia define the terms of the Ukraine crisis"

A question like ‘Did US intelligence-sharing with Ukraine cross a line?’ forgets the fact that it was Russia that crossed the line – by invading Ukraine

In recent weeks, the western public has been obsessed with the question “What goes on in Putin’s mind?” Western pundits wonder: do the people around him tell him the whole truth? Is he ill or going insane? Are we pushing him into a corner where he will see no other way out to save face than to accelerate the conflict into a total war?

We should stop this obsession with the red line, this endless search for the right balance between support for Ukraine and avoiding total war. The “red line” is not an objective fact: Putin himself is redrawing it all the time, and we contribute to his redrawing with our reactions to Russia’s activities. A question like “Did US intelligence-sharing with Ukraine cross a line?” makes us obliterate the basic fact: it was Russia itself which crossed the line, by attacking Ukraine. So instead of perceiving ourselves as a group which just reacts to Putin as an impenetrable evil genius, we should turn the gaze back at ourselves: what do we – the “free west” – want in this affair?

We must analyze the ambiguity of our support of Ukraine with the same cruelty we analyze Russia’s stance. We should reach beyond double standards applied today to the very foundations of European liberalism. Remember how, in the western liberal tradition, colonization was often justified in the terms of the rights of working people. John Locke, the great Enlightenment philosopher and advocate of human rights, justified white settlers grabbing land from Native Americans with a strange left-sounding argument against excessive private property. His premise was that an individual should be allowed to own only as much land as he is able to use productively, not large tracts of land that he is not able to use (and then eventually rents to others). In North America, as he saw it, Natives were using vast tracts of land mostly just for hunting, and the white settlers who wanted to use it for intense agriculture had the right to seize it for the benefit of humanity.

In the ongoing Ukraine crisis, both sides present their acts as something they simply had to do: the west had to help Ukraine remain free and independent; Russia was compelled to intervene militarily to protect its safety. The latest example: the Russian foreign ministry claiming Russia will be “forced to take retaliatory steps” if Finland joins Nato. No, it will not be “forced”, in the same way that Russia was not “forced” to attack Ukraine. This decision appears “forced” only if one accepts the whole set of ideological and geopolitical assumptions that sustain Russian politics.

These assumptions have to be analyzed closely, without any taboos. One often hears that we should draw a strict line of separation between Putin’s politics and the great Russian culture, but this line of separation is much more porous than it may appear. We should resolutely reject the idea that, after years of patiently trying to resolve the Ukrainian crisis through negotiations, Russia was finally forced/compelled to attack Ukraine – one is never forced to attack and annihilate a whole country. The roots are much deeper; I am ready to call them properly metaphysical.

One is never forced to attack and annihilate a whole country

Anatoly Chubais, the father of Russian oligarchs (he orchestrated Russia’s rapid privatization in 1992), said in 2004: “I’ve reread all of Dostoevsky over the past three months. And I feel nothing but almost physical hatred for the man. He is certainly a genius, but his idea of Russians as special, holy people, his cult of suffering and the false choices he presents make me want to tear him to pieces.” As much as I dislike Chubais for his politics, I think he is right about Dostoevsky, who provided the “deepest” expression of the opposition between Europe and Russia: individualism versus collective spirit, materialist hedonism versus the spirit of sacrifice.

Russia now presents its invasion as a new step in the fight for decolonization, against western globalization. In a text published earlier this month, Dmitry Medvedev, the ex-president of Russia and now the deputy secretary of the security council of the Russian Federation, wrote that “the world is waiting for the collapse of the idea of an American-centric world and the emergence of new international alliances based on pragmatic criteria.” (“Pragmatic criteria” means disregard for universal human rights, of course.)

So we should also draw red lines, but in a way which makes clear our solidarity with the third world. Medvedev predicts that, because of the war in Ukraine, “in some states, hunger may occur due to the food crisis” – a statement of breathtaking cynicism. As of May 2022, about 25m metric tons of grain are slowly rotting in Odesa, on ships or in silos, since the port is blocked by the Russian navy. “The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) has warned that millions of people are ‘marching towards starvation’ unless ports in southern Ukraine which have been closed because of the war, are reopened,” Newsweek reports. Europe now promises to help Ukraine transport the grain by railway and truck – but this is clearly not enough. A step more is needed: a clear demand to open the port for the export of grain, inclusive of sending protective military ships there. It’s not about Ukraine, it’s about the hunger of hundreds of millions in Africa and Asia. Here should the red line be drawn.

The Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, recently said: “Imagine [the Ukraine war] is happening in Africa, or the Middle East. Imagine Ukraine is Palestine. Imagine Russia is the United States.” As expected, comparing the conflict in Ukraine with the plight of the Palestinians “offended many Israelis, who believe there are no similarities”, Newsweek noted. “For example, many point out that Ukraine is a sovereign, democratic country, but don’t consider Palestine as a state.” Of course Palestine is not a state because Israel denies its right to be a state – in the same way Russia denies the right of Ukraine to be a sovereign state. As much as I find Lavrov’s remarks repulsive, he sometimes deftly manipulates the truth.

Yes, the liberal west is hypocritical, applying its high standards very selectively. But hypocrisy means you violate the standards you proclaim, and in this way you open yourself up to inherent criticism – when we criticize the liberal west, we use its own standards. What Russia is offering is a world without hypocrisy – because it is without global ethical standards, practicing just pragmatic “respect” for differences. We have seen clearly what this means when, after the Taliban took over in Afghanistan, they instantly made a deal with China. China accepts the new Afghanistan while Taliban will ignore what China is doing to Uyghurs – this is, in nuce, the new globalization advocated by Russia. And the only way to defend what is worth saving in our liberal tradition is to ruthlessly insist on its universality. The moment we apply double standards, we are no less “pragmatic” than Russia.

Sunday, May 22, 2022

Non-Representative Art

Slavoj Zizek, "The Political Implications of Non-Representative Art"

In his Philosophy of History, Hegel provided a wonderful characterization of Thucydides’s book on the Peloponnesian war: “his immortal work is the absolute gain which humanity has derived from that contest.” One should read this judgment in all its naivety: in a way, from the standpoint of the world history, the Peloponnesian war took place so that Thucydides could write a book on it. What if something similar holds for the relationship between the explosion of modernism and First World War, but in the opposite direction? The Great War was not the traumatic break that shattered late nineteenth-century progressism, but a reaction to the true threat to the established order: the explosion of vanguard art, scientific and political, which undermined the established worldview. This included artistic modernism in literature – from Kafka to Joyce, in music – Schoenberg and Stravinsky, in painting – Picasso, Malevitch, Kandinsky, in psychoanalysis, relativity theory and quantum physics, the rise of Social Democracy…

The rupture – condensed in 1913, the annus mirabilis of artistic vanguard – was so shattering in its opening of new spaces that, in a speculative historiography, one is even tempted to claim that the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 was, from the “spiritual” standpoint, a reaction to this Event of rupture – or, to paraphrase Hegel, that the horror of the World War I is the price humanity had to pay for waging the immortal artistic revolution of the years just prior to the war. In other words, one has to turn around the pseudo-deep insight on how Schoenberg et al prefigured the horrors of twentieth-century war: what if the true Event were 1913? It is crucial to focus on this intermediate explosive moment between the complacency of late-nineteenth century and the catastrophe of World War I. 1914 was not the awakening from slumber, but the forceful and violent return of patriotic sleep, destined to block the true awakening. The fact that Fascists and other patriots hated the vanguard entartete Kunst is not a marginal detail but a key feature of Fascism. It is against this background that we should approach the relationship between modern art and the horrors of twentieth-century history.

In his Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911), Wassily Kandinsky develops the idea of how every artwork influences the spectator not through its subject matter but through a certain choice of colors and forms. In this sense, Kandinsky sees “high art” not as the thematization of a neutral medium, which represents nothing, but as having its own operational goal, namely irrational, subconscious influence on the spectator. Particular colors and forms influence the psyche of spectators and produce specific moods in them:“Here the individual is placed not outside the artwork or in front of it but inside the artwork, and totally immersed in it. Such an artificial environment can create a powerful subconscious effect on the spectator, who becomes a visitor to, if not a prisoner of, the artwork… This approach to art does not propagate irrationality, it relies on an even more radical spiritualism: spiritual meaning is inscribed already into the form itself, not only into the content the work of art represents.”[1]However, a quite naïve problem immediately arises here: if the specific form of a work of art produces moods of anxiety, discontent and disorientation, does it not deprive itself of any emancipatory dimension? Does it not propagate irrational pessimism and hopelessness? This is how abstract art (as well as atonal music and free-association writing) were perceived by both poles of the political spectrum in 1930s.

In 1938, during the Spanish Civil War, the French poet, artist, and architect of Slovene origins Alphonse Laurencic relied on Kandinsky’s theories of color and form to decorate cells at a prison in Barcelona where Republicans held captured Francoists. He designed each cell like an avant-garde art installation, so that the compositions of color and form inside the cells were chosen with the goal of causing the prisoners to experience disorientation, depression, and deep sadness:“During the trial Laurencic revealed he was inspired by modern artists, such as surrealist Salvador Dali and Bauhaus artist Wassily Kandinsky, to create the torture cells /…/ Laurencic told the court the cells, in Barcelona, featured sloping beds at a 20-degree angle that were almost impossible to sleep on.They also had irregularly shaped bricks on the floor that prevented prisoners from walking backwards or forwards, the trial papers said. The walls in the 6ft x 3ft cells were covered in surrealist patterns designed to make prisoners distressed and confused, the report continued, and lighting effects were used to make the artwork even more dizzying. Some of them had a stone seat designed to make occupants instantly slide to the floor, while other cells were painted in tar and became stiflingly hot in the summer.”

Indeed, later the prisoners held in these so-called “psychotechnic” cells did report extreme negative moods and psychological suffering due to their visual environment. Here, the mood becomes the message—the message that coincides with the medium. The power of this message is shown in Himmler’s reaction to the cells: he visited the psychotechnic cells after Barcelona was taken by the fascists and said that the cells showed the “cruelty of Communism.” They looked like Bauhaus installations and, thus, Himmler understood them as a manifestation of Kulturbolschevismus (cultural Bolshevism). No wonder Laurencic was put on trial and executed in 1939.

But the paradox is that orthodox Stalinist Marxism advocated the same thesis, just in the opposite direction. In the 1930s, writing in Moscow, Georg Lukács diagnosed expressionist “activism” as a precursor to National Socialism. He stressed the “irrational” aspects of expressionism that later, according to his analysis, culminated in Nazi ideology. Along the same lines, Ilya Ehrenburg wrote at that time about the surrealists: “For them a woman means conformism. They preach onanism, pederasty, fetishism, exhibitionism, and even sodomy.”[2] As late as 1963, in a famous pamphlet called Why I Am Not a Modernist, Soviet art critic Mikhail Lifshitz (a close friend and collaborator of Lukács in the 1930s) repeated the same point: modernism is cultural fascism because it celebrates irrationality and anti-humanism. He wrote:“So, why am I not a modernist? Why does the slightest hint of such ideas in art and philosophy provoke my innermost protest? Because in my eyes modernism is linked to the darkest psychological facts of our time. Among them are a cult of power, a joy at destruction, a love for brutality, a thirst for a thoughtless life and blind obedience /…/ The conventional collaborationism of academics and writers with the reactionary policies of imperialist states is nothing compared to the gospel of new barbarity implicit to even the most heartfelt and innocent modernist pursuits. The former is like an official church, based on the observance of traditional rites. The latter is a social movement of voluntary obscurantism and modern mysticism. There can be no two opinions as to which of the two poses a greater public danger.”[3]In short, modernism is a much greater danger than Fascism… While modernism is Fascist for Soviet Marxism, it is Communist for the Fascists. (There are exceptions on both sides, of course: futurism was appropriated by Italian Fascism as well as by the Soviet art in the 1920s.) On the opposite side, the realism of representation is “totalitarian” for Western modernists who see in anti-representative modern art the liberation of the medium from the message it is supposed to transmit: the message is (in) the medium itself, not in what the medium represents…[4] But the truly surprising fact is that today some cognitivists propagate the same anti-modernist stance, claiming that a good traditional taste for beauty as a source of pleasure is grounded in our nature, so that we should trust people’s taste. Here is what Steven Pinker wrote in this regard:“The dominant theories of elite art and criticism in the 20th century grew out of a militant denial of human nature. One legacy is ugly, baffling, and insulting art. The other is pretentious and unintelligible scholarship. And they’re surprised that people are staying away in droves?”[5]Such a stance is not just gaining traction among some theoreticians, but it is also spreading among Rightist populists. In Slovenia, the Rightists are elevating national folk music into the emblem of being a true Slovene, and are attacking its critics as traitors to Slovene nationhood… The proponents of the idea that the sense of artistic beauty and pleasure is grounded in our nature denounce the modernist “desire to destroy beauty” as an ideological moment of elitist globalism. In a naïve sense, they are making a valuable point: modern art reproduces horror, anxiety and dissonances, which characterize our social being. The question we should ask here is: so why is reproducing anxiety and horror in art subversive, not merely imitating and thereby sustaining the existing alienated social life? The answer is simple: just bringing up anxieties and dissonances is in itself an act of liberation, which enables us to regain a distance towards the existing order. To see this, we have to accept the Hegelian position of Adorno: art is not about pleasure or the experience of beauty; art is a medium of truth, the truth of our human condition in a given historical epoch. And in our epoch, after the modernist break, sticking to the tradition of tonal music or realist painting is as such a fake.

Why? Let’s return to Hegel, to his notion of the end of art. Hegel’s fateful limitation was that his notion of art remained within the confines of classical representative art: he was unable to consider the possibility of what we call abstract (nonfigurative) art, or, for that matter, atonal music, or literature which reflexively focuses on its own process of writing, etc. The truly interesting question here is in what way this limitation—remaining within the constraints of the classical notion of representative art—is linked to what Robert Pippin detects as Hegel’s other limitation, namely his inability to detect the alienation/antagonism that persists even in a modern rational society where individuals attain their formal freedom and mutual recognition. In what way—and why—can this persisting unfreedom, unease, dislocation in a modern free society be properly articulated, brought to light, in an art which is no longer constrained to the representative model? Is it that the modern unease, unfreedom in the very form of formal freedom, servitude in the very form of autonomy, and, more fundamentally, anxiety and perplexity caused by that very autonomy, reach so deep into the very ontological foundations of our being that they can be expressed only in an art form which destabilizes and denaturalizes the most elementary coordinates of our sense of reality? So, for Pippin, Hegel’s “greatest failure” is that he“never seemed very concerned about [the] potential instability in the modern world, about citizens of the same ethical commonwealth potentially losing so much common ground and common confidence that a general irresolvability of any of these possible conflicts becomes ever more apparent, the kind of high challenge and low expectations we see in all those vacant looks. . . . He does not worry much because his general theory about the gradual actual historical achievement of some mutual recognitive status, a historical claim that has come to look like the least plausible aspect of Hegel’s account and that is connected with our resistance to his proclamations about art as a thing of the past.”[6And Pippin himself designates as the core of this new dissatisfaction class division and struggle (here, of course, class is to be opposed to castes, estates, and other hierarchies). A fundamental ambiguity thus characterizes the disturbing and disorienting effect of Manet’s paintings: yes, they indicate the “alienation” of modern individuals who lack a proper place within a society traversed by radical antagonisms, individuals deprived of the intersubjective space of collective mutual recognition and understanding; however, they simultaneously generate and reflect a liberating effect (the individuals they depict appear as no longer bound to a specific place in the social hierarchy).

Pippin is right to point out that, in his proclamation of the end of art (as the highest expression of the absolute), Hegel is paradoxically not idealist enough. What Hegel doesn’t see is not simply some post-Hegelian dimension totally outside his grasp, but the very “Hegelian” dimension of the analyzed phenomenon. The same goes for economy: what Marx demonstrated in his Capital is how the self-reproduction of capital obeys the logic of the Hegelian dialectical process of a substance-subject, which retroactively posits its own presuppositions. However, Hegel himself missed this dimension—his notion of industrial revolution was the Adam-Smith-type manufacture where the work process was still that of combined individuals using tools, not yet a factory where the machinery set the rhythm and individual workers were de facto reduced to organs serving the machinery, to its appendices. This is why Hegel could not yet imagine the way abstraction rules in developed capitalism: this abstraction is not only in our (financial speculator’s) misperception of social reality, but it is “real” in the precise sense of determining the structure of the very material social processes. The fate of whole strata of population and sometimes of whole countries can be decided by the “solipsistic” speculative dance of capital, which pursues its goal of profitability in a blessed indifference to how its movement will affect social reality. Therein resides the fundamental systemic violence of capitalism, much more uncanny than the direct precapitalist socio-ideological violence: this violence is no longer attributable to concrete individuals and their “evil” intentions, but is purely “objective,” systemic, anonymous.

And in an exact homology to this reign of abstraction in capitalism, Hegel was paradoxically not idealist enough to imagine the reign of abstraction in art. That is to say, in the same way that in the domain of economy he wasn’t able to discern the self-mediating Notion which structured the economic reality of production, distribution, exchange, and consumption, he wasn’t able to discern the Notional content of a painting which mediates and regulates its form (shapes, colors) at a level that is more basic than the content represented (pictured) in a painting. In other words, “abstract painting” mediates/reflects sensuality at a non-representative level.[7]

APPENDIX: AM I NOW ASHAMED OF ONCE PUBLISHING IN “RUSSIA TODAY”?

No, absolutely not! Here is the main reason.

A news item passed largely unnoticed while our eyes are mostly on the Ukraine war: on April 20, 2022, Julian Assange moved one step closer to being extradited to the United States, where he is set to be tried under the Espionage Act. A London court issued a formal extradition order in a hearing Wednesday, leaving UK Home Secretary Priti Patel (the one who proposed sending refugees who arrived to the UK to Rwanda) to rubber-stamp his transfer to the US. If convicted, Assange faces up to 175 years in prison… So, yes, we should fully support Ukrainian resistance. And, yes, we should defend Western freedoms. Just imagine with shudder what would have happened to Chelsea Manning if she were Russian! But our Western freedom also has limits, which we should never lose out of our sight, especially in moments like this when “the fight for freedom” is on everyone’s lips.

We hear these days the demand that Putin should be brought to the Hague tribunal for Russian war crimes in Ukraine. OK, but how can the US demand this, while they do not recognize the competence of the Hague tribunal for their own citizens? And, to add insult to injury, how can they demand the extradition of Assange to the US when Assange is not a US citizen, was not involved in any spysing against the US, plus all he did was to make public what are undoubtedly the US war crimes (recall just the famous video clip of US snipers killing Iraqi civilians)? Assange is under threat of getting 175 years of prison for just disclosing US crimes, which are beyond reproach… Not even to mention the long list of crimes of the US Presidents!

If Putin belongs in the Hague, why not also Assange? Why not Bush and Rumsfeld (who is already dead) for the “shock and awe” bombardment of Baghdad? It is as if the guideline of the recent US politics is a weird reversal of the well-known motto of the ecologists: act globally, think locally. This contradiction was best exemplified already back in 2003 by the two-sided pressure the US was exerting on Serbia: the US representatives simultaneously demanded of the Serbian government to deliver suspected war criminals to the Hague court AND to sign the bilateral treaty with the US obliging Serbia not to deliver to any international institution (i.e., to the SAME Hague court) the US citizens suspected of war crimes or other crimes against humanity. No wonder the Serb reaction was one of perplexed fury…

There were things – not only on Assange, but also on the weaknesses of liberal democracy, on the Israeli apartheid politics in the West Bank, on the aberrations of Political Correctness, etc. – which I was simply able to publish in English only there, in Russia Today (RT). If I were to do it in other very marginal sites in the West, the texts would have found a very limited echo. Of course, we have much more freedom in the liberal West, but that’s why prohibitions are all the more conspicuous. The lesson is that Western democracies also have their dirty side, their own censorship, so we have the full right to ruthlessly play one superpower against the other. What I was publishing in RT and what I am now publishing in support of Ukraine are for me parts of the same struggle, in the same way that there is no “contradiction” between the struggle against anti-Semitism and the struggle against what Israel is doing on the West Bank with Palestinians. If we see Ukraine and Assange as a choice, we are lost; we have already sold our soul to the devil.

Far from standing for a utopian position, this necessity of a common struggle is grounded in the very fact of the far-reaching consequences of extreme suffering. In a memorable passage in Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered, Ruth Klüger describes a conversation with “some advanced PhD candidates” in Germany:“one reports how in Jerusalem he made the acquaintance of an old Hungarian Jew who was a survivor of Auschwitz, and yet this man cursed the Arabs and held them all in contempt. How can someone who comes from Auschwitz talk like that? the German asks. I get into the act and argue, perhaps more hotly than need be. What did he expect? Auschwitz was no instructional institution /…/. You learned nothing there, and least of all humanity and tolerance. Absolutely nothing good came out of the concentration camps, I hear myself saying, with my voice rising, and he expects catharsis, purgation, the sort of thing you go to the theatre for? They were the most useless, pointless establishments imaginable.”[8]In short, the extreme horror of Auschwitz did not make it into a place which purifies its surviving victims into ethically sensitive subjects who got rid of all petty egotistic interests; on the contrary, part of the horror of Auschwitz was that it also dehumanized many of its victims, transforming them into brutal insensitive survivors, making it impossible for them to practice the art of balanced ethical judgment. The lesson to be drawn here is a very depressing one: we have to abandon the idea that there is something emancipatory in extreme experiences, that they enable us to clear the mess and open our eyes to the ultimate truth of a situation. Or, as Arthur Koestler, the great anti-Communist convert, put it concisely: “If power corrupts, the reverse is also true; persecution corrupts the victims, though perhaps in subtler and more tragic ways.”

NOW is the time to insist on equal treatment and to address the same critical questions to Russia and to the West. Yes, we are all now Ukrainians – in the sense that every nation has the right to defend itself like Ukraine does.

Notes:[1] Boris Groys, quoted from The Cold War between the Medium and the Message: Western Modernism vs. Socialist Realism – Journal #104 November 2019 – e-flux. In my description, I rely heavily on Groys’s text.

[2] Quoted from Groys, op.cit.

[3] Quoted from op.cit.

[4] One should mention here another surprising exception: Irving Reis’s Crack-Up, a noir from 1946 in which the elite proponents of modern non-realist art are presented as corrupted Fascist villains who aim at confusing masses of ordinary people; the film’s hero is an art critic who attacks modern art and defends the taste of ordinary people.

[5] Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature, London: Penguin 2002.

[6] Robert B. Pippin, After the Beautiful: Hegel and the Philosophy of Pictorial Modernism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), p. 69.

[7] I resume here my argumentation from chapter 4 of Disparities, London: Bloomsbury Press 2016.

[8] Ruth Klüger, Still Alive: A Holocaust Girlhood Remembered, New York: The Feminist Press 2003, p. 189.

Saturday, May 21, 2022

The Problem of Neo-Left Liberalism

Mark Fisher, "Exiting the Vampire Castle" (11/22/13)

This summer, I seriously considered withdrawing from any involvement in politics. Exhausted through overwork, incapable of productive activity, I found myself drifting through social networks, feeling my depression and exhaustion increasing.

‘Left-wing’ Twitter can often be a miserable, dispiriting zone. Earlier this year, there were some high-profile twitterstorms, in which particular left-identifying figures were ‘called out’ and condemned. What these figures had said was sometimes objectionable; but nevertheless, the way in which they were personally vilified and hounded left a horrible residue: the stench of bad conscience and witch-hunting moralism. The reason I didn’t speak out on any of these incidents, I’m ashamed to say, was fear. The bullies were in another part of the playground. I didn’t want to attract their attention to me.

The open savagery of these exchanges was accompanied by something more pervasive, and for that reason perhaps more debilitating: an atmosphere of snarky resentment. The most frequent object of this resentment is Owen Jones, and the attacks on Jones – the person most responsible for raising class consciousness in the UK in the last few years – were one of the reasons I was so dejected. If this is what happens to a left-winger who is actually succeeding in taking the struggle to the centre ground of British life, why would anyone want to follow him into the mainstream? Is the only way to avoid this drip-feed of abuse to remain in a position of impotent marginality?

One of the things that broke me out of this depressive stupor was going to the People’s Assembly in Ipswich, near where I live. The People’s Assembly had been greeted with the usual sneers and snarks. This was, we were told, a useless stunt, in which media leftists, including Jones, were aggrandising themselves in yet another display of top-down celebrity culture. What actually happened at the Assembly in Ipswich was very different to this caricature. The first half of the evening – culminating in a rousing speech by Owen Jones – was certainly led by the top-table speakers. But the second half of the meeting saw working class activists from all over Suffolk talking to each other, supporting one another, sharing experiences and strategies. Far from being another example of hierarchical leftism, the People’s Assembly was an example of how the vertical can be combined with the horizontal: media power and charisma could draw people who hadn’t previously been to a political meeting into the room, where they could talk and strategise with seasoned activists. The atmosphere was anti-racist and anti-sexist, but refreshingly free of the paralysing feeling of guilt and suspicion which hangs over left-wing twitter like an acrid, stifling fog.

Then there was Russell Brand. I’ve long been an admirer of Brand – one of the few big-name comedians on the current scene to come from a working class background. Over the last few years, there has been a gradual but remorseless embourgeoisement of television comedy, with preposterous ultra-posh nincompoop Michael McIntyre and a dreary drizzle of bland graduate chancers dominating the stage.

The day before Brand’s now famous interview with Jeremy Paxman was broadcast on Newsnight, I had seen Brand’s stand-up show the Messiah Complex in Ipswich. The show was defiantly pro-immigrant, pro-communist, anti-homophobic, saturated with working class intelligence and not afraid to show it, and queer in the way that popular culture used to be (i.e. nothing to do with the sour-faced identitarian piety foisted upon us by moralisers on the post-structuralist ‘left’). Malcolm X, Che, politics as a psychedelic dismantling of existing reality: this was communism as something cool, sexy and proletarian, instead of a finger-wagging sermon.

The next night, it was clear that Brand’s appearance had produced a moment of splitting. For some of us, Brand’s forensic take-down of Paxman was intensely moving, miraculous; I couldn’t remember the last time a person from a working class background had been given the space to so consummately destroy a class ‘superior’ using intelligence and reason. This wasn’t Johnny Rotten swearing at Bill Grundy – an act of antagonism which confirmed rather than challenged class stereotypes. Brand had outwitted Paxman – and the use of humour was what separated Brand from the dourness of so much ‘leftism’. Brand makes people feel good about themselves; whereas the moralising left specialises in making people feed bad, and is not happy until their heads are bent in guilt and self-loathing.

The moralising left quickly ensured that the story was not about Brand’s extraordinary breach of the bland conventions of mainstream media ‘debate’, nor about his claim that revolution was going to happen. (This last claim could only be heard by the cloth-eared petit-bourgeois narcissistic ‘left’ as Brand saying that he wanted to lead the revolution – something that they responded to with typical resentment: ‘I don’t need a jumped-up celebrity to lead me‘.) For the moralisers, the dominant story was to be about Brand’s personal conduct – specifically his sexism. In the febrile McCarthyite atmosphere fermented by the moralising left, remarks that could be construed as sexist mean that Brand is a sexist, which also meant that he is a misogynist. Cut and dried, finished, condemned

It is right that Brand, like any of us, should answer for his behaviour and the language that he uses. But such questioning should take place in an atmosphere of comradeship and solidarity, and probably not in public in the first instance – although when Brand was questioned about sexism by Mehdi Hasan, he displayed exactly the kind of good-humoured humility that was entirely lacking in the stony faces of those who had judged him. “I don’t think I’m sexist, But I remember my grandmother, the loveliest person I‘ve ever known, but she was racist, but I don’t think she knew. I don’t know if I have some cultural hangover, I know that I have a great love of proletariat linguistics, like ‘darling’ and ‘bird’, so if women think I’m sexist they’re in a better position to judge than I am, so I’ll work on that.”

Brand’s intervention was not a bid for leadership; it was an inspiration, a call to arms. And I for one was inspired. Where a few months before, I would have stayed silent as the PoshLeft moralisers subjected Brand to their kangaroo courts and character assassinations – with ‘evidence’ usually gleaned from the right-wing press, always available to lend a hand – this time I was prepared to take them on. The response to Brand quickly became as significant as the Paxman exchange itself. As Laura Oldfield Ford pointed out, this was a clarifying moment. And one of the things that was clarified for me was the way in which, in recent years, so much of the self-styled ‘left’ has suppressed the question of class.

Class consciousness is fragile and fleeting. The petit bourgeoisie which dominates the academy and the culture industry has all kinds of subtle deflections and pre-emptions which prevent the topic even coming up, and then, if it does come up, they make one think it is a terrible impertinence, a breach of etiquette, to raise it. I’ve been speaking now at left-wing, anti-capitalist events for years, but I’ve rarely talked – or been asked to talk – about class in public.